First, we human beings needed to survive. It was in our nature to survive. And so, we built cities, isolating ourselves from nature—and doing so, invented philosophies about how we were separate from the realm of other animals. However, in our cities today, all across the world, nature intrudes on our daily lives. In this corner of the world which we carved out for ourselves, nature, most noticeably in animals, lurks everywhere. In our minds, with our tendency for hierarchization, not all animals are created equal. Much has already been said about the meaning and the symbol of the rat, but not as much about its avian equivalent, the so-called “flying rat,” otherwise known as the common pigeon.

They are known as pests. Poisons have been used for population control. Spikes are placed over the ledges of buildings to stop them from nesting. A similar method is used on the floors of nooks and recesses of certain buildings to stop homeless people, equally undesirable, from sleeping there. And yet, they remain, both pigeons and the homeless, as the ever-present constants of all the cities of the world. (Eliminating homelessness would be a beneficial thing indeed, a humanistic achievement—but to rid ourselves of pigeons?)

During World War II, during the siege of Leningrad, there were no pigeons. In the besieged city, where two million people died of starvation, people hunted pigeons—in part because of their abundance, and also because they were so tame. Having eradicated them—having already depleted all other animals—some people resorted to cannibalism. From this fact there are many conclusions one could come to, regarding our human nature. One could be this: that between the comfortable perception of our humanity—of how we see ourselves—and total savagery, the last line of defense is the pigeons.

All manner of human beings, from all walks of life, have encountered these birds. From the sidewalks of busy intersections to the sprawling city parks where they nest, breed; scrounge for food, and fly about. On park benches, the loneliest people feed them and count on their company, finding comfort in them.

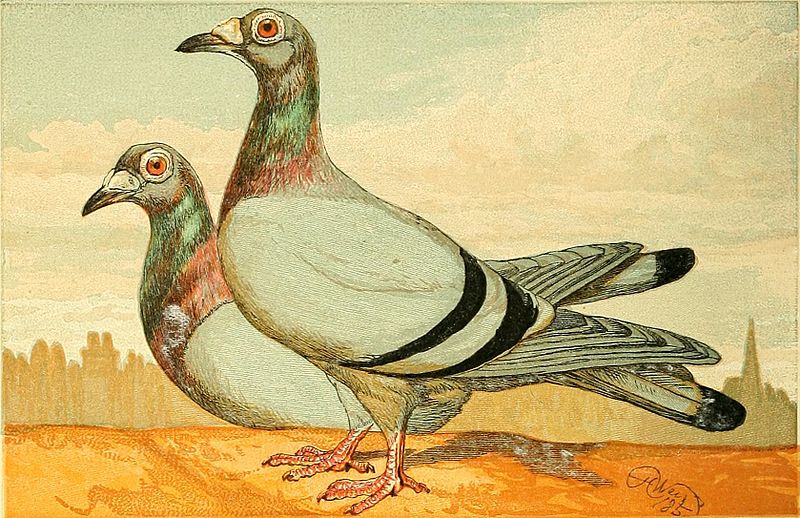

In my own life, I spent many hours watching them—sensing a connection from their dark eyes surrounded by an orange eye-ring; watching how they bobbed their heads to walk around; how they cooed and rubbed their beaks together in courting. One has only to look to see a beautiful bird, so tame that it would eat from your hand. Often I would look at them, and remember a story my mother told me about her childhood in Mexico, about having to raise them for food because she was so poor. And in those moments, I feel gratitude for these gentle birds with their iridescent wings—these creatures, capable of flight, that could easily fly away, but that choose to remain with us in our cities.

—GSO